According to noted Japanese author and authority on the art

of Japanese prints, Narazaki Muneshige, although he was not well known inside

Japan, Kawase Hasui (1883 – 1957) was quite famous in the West, and one of the

three greatest woodblock print artists of Japan, standing in the company of

Hokusai and Hiroshige. A master of the Shin Hanga (新版画) or “new woodcut (block) prints”) movement of the early to

mid-twentieth century, his work was declared to be a Living National Treasure.

Hasui was born in Tokyo, the son of a well-to-do merchant

family. Although later a source of conflict within the family, he was given the

opportunity at an early age to study Western-style painting under famed

watercolorist and print maker Saburosuke Okada (1869 – 1939) who instructed the

boy in the arts of both watercolor and oil painting. As his enthusiasm for art

grew, his family’s did not, eventually attempting to block his studies in any

way possible. To their mind, he was destined to work at the family business.

The problem was ultimately solved when one of his sisters married a shop

employee and took over the family business in his stead.

When he was twenty-six, Kawase asked to be accepted as a

student of traditional Japanese-style painter Kiyokata Kaburagi (1878 – 1972),

a master of the bijinga genre popular at the time. Kaburagi however regarded

Kawase as being too old for an apprenticeship and rejected the young man.

Undaunted however, a determined Kawase was back two years later and Kaburagi

relented, recognizing the young man’s talents and ultimately introducing him to

Watanabe Shozaburo (1885 – 1962), the famed print publisher and central force

behind the shin-hanga movement, beginning what would ultimately be a long,

close, relationship.

Watanabe was, in fact, the initiator, the “spiritual” and

the driving commercial force behind shin-hanga. At a time when the popularity

of traditional ukiyo-e printmaking was in rapid decline and approaching actual

extinction, it was Watanabe who gathered together a small group of literally

starving artists and gave them commissions for prints. At the time, ukiyo-e had

been a mass-consumption product; one which stood little chance of survival in

competition with the growing popularity of photography. Watanabe’s commissioned

prints were however targeted to a more specific audience: lovers of Japanese

art, outside of Japan.

From 1918 through 1923, Kawase produced over a hundred

prints, all published by Watanabe, and primarily exported to the United States.

However, no good deed goes unpunished. On September 1, 1923 Japan was struck by

one of the worst earthquakes ever to strike the country up until that time.

Over 140,000 people died in the Great Kanto Earthquake and the resultant fires

which raged through the Tokyō – Yokohama region. Watanabe’s print shop was

destroyed by fire and with it went all of Kawase’s woodblocks. Adding insult to

injury, Kawase’s home was destroyed and with it went all of his sketchbooks.

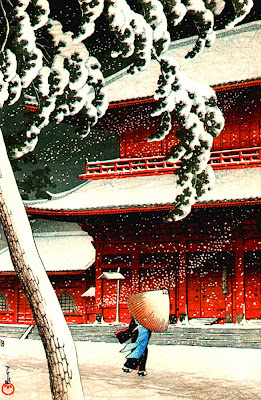

During his career, Kawase produced over four hundred

woodblocks for Watanabe, many of which were elegant landscape prints, often

showing night scenes, snow, and rain, demonstrating his ability to create

distinct moods in his work. Often there are no people, choosing instead to leave

the viewer with a feeling of peace and tranquility; however with an undertone

that was frequently strange or even uncanny.

Unlike many of his contemporaries, he did not work at home

but rather chose to work in the field — on the spot — often travelling around

the country with the intent of creating his prints from a “live” view. He would

sketch in the field, then return to his inn where he would add color to the drafts.

Later he would return to Tokyō where the carvers and printers would be given

his work. But that is not to say that once the sketches were turned over for

production that he divorced himself from the process. Rather, he was involved

in the entire process from sketch, to cutting of the blocks (one block per

color plus a “key” block for the outlines — products of teamwork between the

artist, the carver, the printer, and ultimately the publisher.

Hasui was a tiny man with poor vision, requiring him to wear

thick glasses. Often, in order to draw sketch details, he actually had to move

up close to an object. While he never became rich, he was able to make a

sufficient living; despite the fact that he lost his home twice: once to the

Great Kanto Earthquake and then again to Allied bombing of Tokyo during World

War II.

In 1956 Kawase was named as a Living National Treasure by

the Emperor: the greatest honor a Japanese artist can receive from his country.